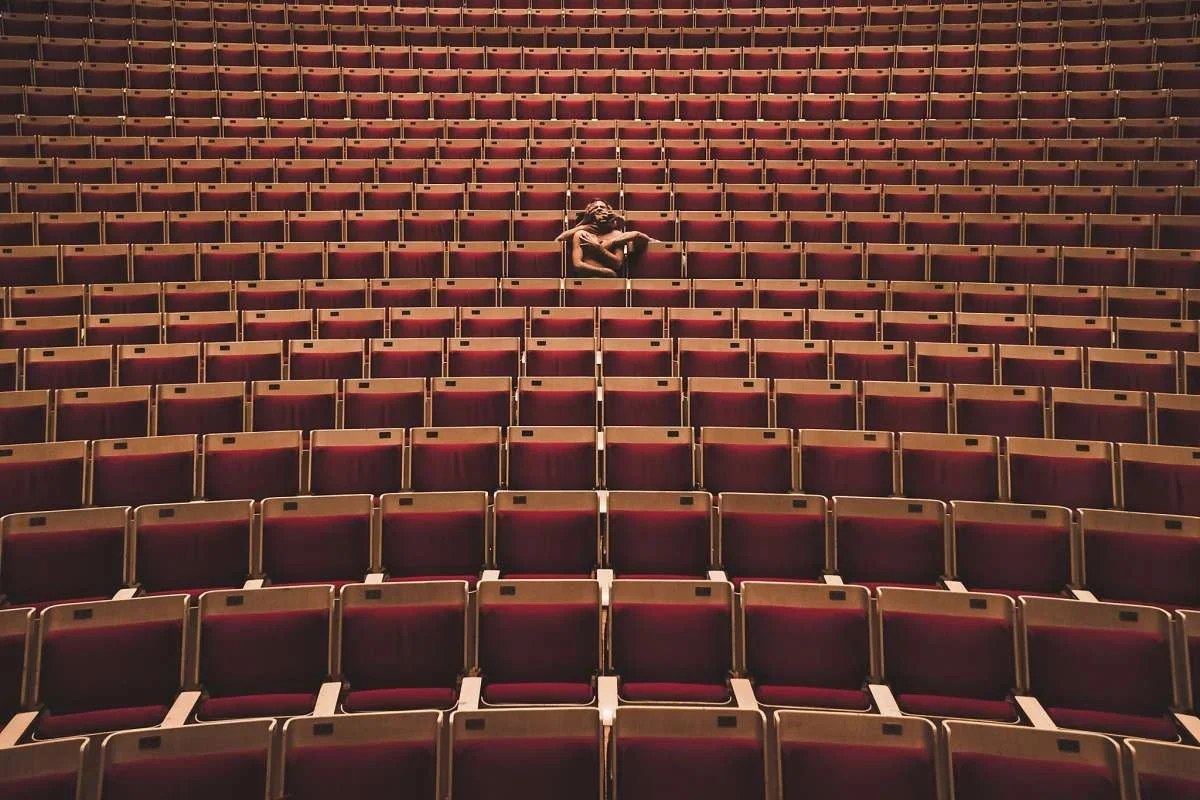

The ritual of gathering in rooms alongside our fellows to pay witness to a live performance, made by other humans and happening in real time, seems to be becoming almost quaint. I haven’t done any sort of official study, but as someone who spends a lot of time in performance spaces, I can attest to the undeniable fact that audience sizes are dwindling. Why spend precious time, money and energy attending a concert, a play, an opera or a dance recital when the easier and cheaper thing to do is just stay in and watch something?

The latter is certainly what we’re being culturally prompted to do, given the current, constant hype devoted to all things glowing and streaming. With a deluge of digital content being created and released all the time, including simultaneous, on-demand access to first-run releases like “The Irishman,” there would seem to be ever fewer reasons to seek out entertainment outside the home. Have we unconsciously entered the twilight of the performing arts?

My fellow performers, artists whose lives are devoted to getting on stages night after night, would be horrified by this question, but not just for the obvious reasons. The triumph of streaming is about more than livelihoods being threatened, of older modes of entertainment being eclipsed by a shinier, more efficient replacement. The endangerment of live performance is as paradigm-shifting a notion as climate change, as potentially damaging to our inner, emotional lives as warming oceans and deforestation are to our physical selves and the planet we inhabit.

Most of us have, at some point in our lives, been deeply affected by something we’ve seen live, in a venue of some kind. Something essential to who were are is activated, something not often accessible in our everyday lives, and fundamentally absent from the experience of looking at a screen. For some fixed amount of time, we observe as artists serving as our proxies reveal us to ourselves. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, our collective spirit is elevated.

We are reminded of what is important, and what is not. We feel a connection to ourselves, and to others. We feel an overwhelming sense of being alive.

This was my experience after watching “The Michaels,” Richard Nelson’s latest play (he also directed it), which recently finished its run at the Public Theater in New York City. Most of the action, such as it was, involved people sitting around at tables, in chairs, talking. There was some everyday furniture, a countertop, a sink, a stove, some lights. Nothing fancy, and no dumb theatrics. The drinking glasses didn’t match, and that seemed right. The sink and the stove were practicals: They worked, and are used. Real liquid was dispensed from bottles. The actors spoke in conversational tones (a phalanx of thin overhanging microphones absolved them from any actorly responsibility to project their voices). None of this had anything to do with the deeper content of the play, but it all combined to make an important agreement with the audience: relax. No need to strain the imagination. Be here now.

So we were. We sat back and watched, and listened, as stories were exchanged, and small talk was made. Food was prepared, cooked and eaten. At one point, a couple of the characters danced. And that was about it. Not much happened, per se, and yet the effect of the production — its simple elegance, its warmth, its gentleness, its authenticity — was so powerful that, when it concluded, the audience was left in stunned silence. Theater, when it’s done well, when it matters, can have this kind of effect.

Ironically, in what was essentially a two-hour gabfest, the greatest drama in “The Michaels” occurred when the talking temporarily ceased. For some minutes during which there was only movement and music, we watched as the extraordinarily nuanced realities of each of the play’s seven characters responded internally to one especially freighted moment, as an exquisitely complex web of relationships, and histories was laid out before us. Everything we saw these people feel (and everything we thus felt ourselves), was communicated through nothing more than facial expressions and body language — not action so much as reaction. In an instant, we caught a glimpse of how profoundly we affect one another in our day-to-day lives, the impact of even our most mundane choices and behaviors, how fiercely we guard our vulnerability. We were confronted with the reality we all share: We’re humans, we die, the world goes on without us. It was a moment so simple, beautiful and terrible that it blindsided us, knocking our wind out in the gentlest possible way.

It was here that Nelson drove home the conviction that seemed to be at the heart of “The Michaels”: that the life force behind our fragile human existence is engagement. As Rose, a terminally ill choreographer, watched her daughter rehearse a dance, she suddenly snapped to life. Her eyes burned with commitment and intensity. Consciousness of her own mortality vanished. To be alive now, to be inspired, focused, connected — that is something that passion can give us, if we are able and brave enough to meet it. It is the grip of life, the nourishing force that gives our existence meaning, defeating death, stopping time. It’s what the greatest performing arts makers do, and it’s what we give back as live audiences. Each needs the other to produce catharsis, something truly experienced only when both are present.

Theater doesn’t always reward us like this, especially in America. Too often, the time, attention and faith we offer it are met with a galling concoction of phoniness, grandiosity and noise. As we encounter yet another soul-crushing experience, we’re left to wonder, again, why we didn’t just stay in and watch that next episode. “The Michaels” was a quietly urgent exhibit of how necessary theatre can be, how vital the performing arts are to our culture, how they serve to remind us of our own humanity, and by so doing, lead us back to our truest selves. Our hearts and minds need these experiences, just as our bodies need sustenance. In their absence, our collective spirit starves, and begins feeding on itself.

There’s no way to stream “The Michaels.” It’s gone now, forever, just like almost everything else that happens on a stage. So don’t wait. If you need a reminder of what you’re doing here, of what life is for, turn off your screen, seek out the best live performance currently offered, and go see it. Now.

Howard Fishman is a performing songwriter, theater maker, educator and culture writer. Twitter: @howardfishman